Note: this part of the Britpop Album Showdown series.

Blur’s journey from late period “Madchester” also-rans to a (mostly) beloved part of the national conscience was quite a ride. If one wanted to be sniffy about them, you would probably point at the dilettantism of frontman and de facto artistic director Damon Albarn.

Arguably, he was Britpop’s McCartney: artistically fertile to the point of inanity – and interested in versatility for versatility’s sake, as evidenced by both Blur’s periodic reinvention to suit his prevailing taste, or his endless, post-Blur stream of exotic side projects.

Back in ’94, Blur had arguably already created the blueprint for Britpop with their 1993 single Poplife – a mini manifesto extolling Blur’s faintly knowingly cynical concern with artifice – possibly pointed at themselves:

“A fervored image of another world

Is nothing in particular now

An imitation comes naturally

But I never really stop to think how

And everyone is a clever clone

A chrome colored clone am I”

Modern Life Is Rubbish had performed moderately well in 1993 and wiped away the Johnny-come-lately ‘baggy’ associations of Blur’s debut to create a new identity for the band as a latter-day Kinks.

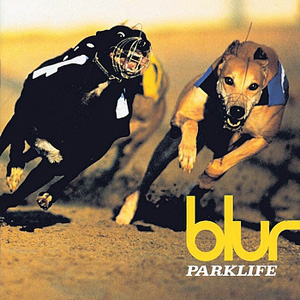

Setting aside this view of Blur as cynics though, it’s hard to argue with their body of work in the second half of the 90s. And hindsight now tells us that in 1994 they were at their commercial and probably artistic peak with the release of Parklife: an album that both catapulted Blur into the premier league of record sales, and galvanised the whole Union-Jack-waving “Cool Britannia” era.

So, here we are. It’s 1994 and Parklife is in front of us. Let’s dive in!

1. Girls and Boys

This glittery, disco stomper is a serious statement of intent. Hanging on a catchy bassline (perhaps distantly related to Wings’ Silly Love Songs (1976)) and a refrain that knowingly references Bob Crewe’s Music to Watch Girls By (1966) the song looks at British youth’s infatuation with misbehaviour on foreign holidays to the Mediterranean with what might be categorised as playful disdain. Sexually transmitted infections caught through careless encounters through a haze of booze and drugs. Albarn’s semi-affectionate disdain is easily traced in the lyrics – pointed as they are at “battery thinkers” who “count their thoughts on one, two, three, four… five fingers”.

Ironically, of course, the chorus also expresses some level of admiration for sexual freedom. If the sixties had “music to watch girls by”, the nineties’ equivalent had:

“Girls who are boys

Who like boys to be girls

Who do boys like they’re girls

Who do girls like they’re boys

Always should be someone you really love”

In many ways, this is the ideal of David Bowie’s vision in Oh! You Pretty Things (Hunky Dory, 1972) but his utopian vision of pansexuality is now seen as something animalistic by the more cynical Albarn: an offshoot of unsupervised lager-fuelled hedonism. And is there a faint trace of finger wagging in that final line: “always should be someone you really love”? I think there is. Cynicism aside, this is clearly a triumph: a jubilant marriage of disco, pop, indie and a lyric that both sides with and condemns its characters.

2. Tracy Jacks

Tracy Jacks is another observational song in the vein of a long and very English tradition of character pieces: a story told about a fictional character used to explore a viewpoint of the world. In this case, the titular Tracy Jacks (male, despite the more traditionally female name) is a civil servant who leaves work one day, catches a train to the seaside, strips naked and runs around until the police are called and he is taken back home. His main complaint? That normality is “just so overrated”.

It’s hard not to detect echoes of another English institution of popular culture here: The Fall and Rise of Reginald Perrin – the opening credits of which showed Leonard Rossiter leaving his clothes on the beach and swimming, naked out to sea – presumably to his death (although, in fact, the series showed that his apparent suicide attempt was actually unsuccessful). It has long been a tradition of English pop songwriters to populate their songs with characters in this sort of vein.

In the end, the lyrical effect is fairly banal, but the rousing shout-a-long yobbishness of the chorus batters the point home with an undeniable gusto – and Albarn’s slack-jawed (and later much-derided) ‘mockney’ vowels are the perfect vehicle for their delivery.

3. End of a Century

A song set in a humdrum domestic scene, End of a Century is very much a state-of-the-nation address wrapped in effortlessly classic songwriting. The unnamed characters in the song are tied to their small lives – plagued by ants in the carpet, getting a little sparkle from morning TV and wearing the same clothes because they “feel the same.” In the latter half of the 90s, there was much discussion about what the end of the century (and, indeed, the millenium) actually meant. To Albarn – like the protagonists of his song – the date is just meaningless background to an ordinary life. If Boys and Girls was part-sneer, End of a Century is far more tender towards its subjects. For all the mundanity of their life, there is a simple humble dignity to their shared existence.

Musically, End of a Century is a great example of what I’d say was Blur’s signature sound. The chord progression is fairly standard, but the interplay of bass and guitar in particular means it is never dull. Later in Blur’s career, as guitarist Graham Coxon tired of Albarn’s pop sensibilities and sought to subvert it with atonal guitar parts (see: the ‘solo’ from 1995’s Country House). Here, however, his playing is inventive, melodic and tricksy – helping to make a fairly mundane chord change into something that really pops.

4. Parklife

Another anthem you say? 1994 model Blur had a warehouse full. The inspired decision to cast mod icon Phil Daniels (star of the Who’s “Quadrophenia” film) and his authentic cockney slur made the song instantly iconic. Spoken word recordings are a rare beast in the charts and the ramblings of Daniels’ character, with their colourful, timeless evocation of a certain strand of “no-nonsense” Englishness quickly found a place on everyone’s lips that summer. Chuck in another barrelhouse chorus and iconic lines like “the dirty pigeons… they love a bit of it” and Parklife became a staple of the nation’s vernacular. Indeed, 20 years later the phrase itself found a second life as a comical rejoinder to the wordy political musings of comedian-turned-political-activist Russell Brand’s own brand of verbiage.

But there’s that word again: character. Daniels is an actor and while not in a song rather than a film, he is playing another one of Albarn’s character – one who again teeters on the edge of stereotype. Did that braces-wearing, swaggering cockernee ever exist outside of the Kinks’ songbook? Rendered moot by the success of the song, it’s worth (perhaps) remembering that Albarn is depicting a world that is both instantly recognisable and probably actually apocryphal: a flipside to the “sceptr’d isle” image favoured by the nation’s great and good – and every bit as fictional.

5. Bank Holiday

Like feeding the sparrows or going insane in a reaction to the mundanity of every day, the modern bank holiday also has a very special place in the English psyche: a day off work dedicated to firing up a barbecue, drinking lager and get sunburned while watching football on the TV. Once again, a stereotype – and possibly one that resonated more deeply in the 90s, with the re-emergence of football as a centrepiece of the country’s culture and the attendant ‘lad culture’. The song itself is an entertaining proto-punk romp which knows not to outstay its welcome, clocking in at well under 2 minutes: an authentic expression of the more boisterous side of the band’s Essex roots.

6. Badhead

Perhaps the first expression of genuine emotion on the album, Badhead is an affectingly pretty song, wreathed in jangling guitars and florid keyboards that in places almost sound Baroque. Lyrically, it seems to take place in a moment where two erstwhile lovers have drifted apart – almost without realising it. Neither party has “really stayed in touch” and the male protagonist at least has lapsed into a kind of numbed boredom – grinning and bearing it rather than getting involved in some kind of proper resolution that would probably end in an argument. A sign of the song’s genuine emotional content can probably be detected in Albarn’s straight-ahead delivery: both gentle and sung in an accent that doesn’t seem exaggerated in the way that, say, the chorus of Parklife does. At last: a glimpse beneath the cynical eye of much of Parklife’s songs and arguably a welcome respite from the slew of shouty sing-a-longs heard to this point.

7. The Debt Collector

Blur’s stylistic diversity and musical playfulness was one of the elements that set them very clearly apart from main rivals Oasis. Indeed, tracks like this – a pootling, brass-band-in-the-park instrumental – were exactly the sort of evidence proferred by those who thought of Blur as too clever by half. Seen in context of the album though, it is an amusing throwaway that serves to maintain the gentle slowing of pace established by Badhead. Musically, it is not without a certain beguiling charm, and behaves exactly as it should: arriving unannounced and leaving with dignified brevity.

8. Far Out

Sequencing of albums is, in the digital world, something of a lost art. The opening salvo of songs were all stomping, rollicking blasts of guitar pop – sometimes bordering on the frenzied. Badhead… The Debt Collector and now this work to change the mood of the album entirely: demonstrating exactly how much this is an album rather than a collection of songs. The only song on the album not penned by Albarn (bassist Alex James stepping up to deliver this) Far Out come from another part of the English pop songwriting tradition whose genesis lies with the cosmic musings of the first iteration of Pink Floyd. Indeed, the laconic delivery and instrumentation (particularly the opening few seconds) could have been dropped onto any Syd Barrett album without seeming out of place for one second. Lyrically and musically, there is little of note here beyond a listing of celestial objects, but the evocative fairground sound remains in keeping with the other songs and maintains the mood that has been established over the last few numbers. Seen less as a song and more of an intro to the “spacey” To The End it fits into the running order with a certain quiet perfection.

9. To The End

A true masterpiece: just shy of 4 minutes of pop perfection. Albarn’s goal – clearly evident in the accompanying video – is to set a love story in the detached style of 1960s/70s French cinema. The male and female character literally talk past another – both in language and meaning. To me, it is a story of miscommunication with an unresolved ending:

He plays down their affair as a passing fling: “We’ve been drinking far too much… neither of us means what they say.”

Meanwhile, she says far less, and with a repetitive detachment – almost as if playing lip service to him: “en plein soleil (in plain sunlight) … jusqu’à la fin (until the end) … en plein amour (in plain love)”

Or, to put it another way: he is drunk and she is bored. An irresolved meeting – tantalisingly inconclusive in its nature, but beguiling because of that very fact. Even the apparently cathartic chorus – which one might expect to offer clarification says only that “it looks like we’ve made it to the end.” Looks like? And what end?

Musically, it is a thing of soaring beauty – a pulsing rhythm track, overlaid with cinematic guitars and swooping strings that remain utterly timeless over 20 years later.

10.London Loves

The theme of detachment evidenced in To The End is continued through London Loves. This time however the music and themes reflect more the cold, analytical eye displayed on the first few tracks. It is a view both of one city and one of its nameless denizens. As with End of a Century, “everybody’s at it.” Whereas in that song the “it” was sex, here it is love – as if love is just another activity like driving a car or coughing up tar at the traffic lights.

“Its love you like, and everyone’s at it

And words are cheap when the mind is elastic

He loves the violence

Keeps ticking over

So sleep together

Before today is sold forever”

As with all the characters on Parklife, the unknown character at its heart is resigned to and trapped to his fate. If you’re getting a sense of cynicism from this album, then you’re far from alone. Indeed, this kind of look-at-all-the-normal-boring-people vibe has something of the misanthropic air of Roger Waters’ lyrics for Pink Floyd. Maybe, subconsciously, this informed the psychological division between Blur and Oasis.

Musically, this is by far the least attractive song on the album. Angular riffs clash with dissonant guitar parts and a robotic rhythm track. In tandem with the lyrical concern with the grinding nature of modern urban life this makes perfect sense – but it also renders the song more tolerable than likeable.

11. Clover Over Dover

Musically, Clover Over Dover is more akin to material found on Park Life’s predecessor Modern Life is Rubbish – with a slippery guitar figure punctuating a sinuous backing track that is primarily distinguished by the use of a harpischord. As with Tracy Jacks, the song seems to be concerned with the suicidal impulses of someone trapped by their life – although they are looking for someone else to ‘push them over,’ suggesting they lack the conviction to do it themselves. There is also a kind of resigned acceptance that the protagonist’s life isn’t worth very much (seeing a bit of the recurring misanthropy I mentioned earlier here?) All the guy think’s he’ll be is a ‘cautionary tale’ and he asked not to be buried because he isn’t worth anything.

If that lyrical content sounds a little dark for a tune that is – in the context of this album – quite upbeat, then I’d be inclined to agree with you. The White Cliffs of Dover are quite central to the mythologised image of England, so on an album so concerned with the English identity you might expect something with a little more substance. On the whole, the track works better as a piece of music than as a lyrical idea.

13. Magic America

Another ‘character’ piece, this follows the experience of the fictional Bill Barrett – who is suckered into buying into the American Dream. Damon Albarn was very consciously reacting to the creeping Americanisation of Britain at the time – and the whole Britpop movement (so far as it existed) was driven by the attempt to re-establish a British identity after the grunge invasion of the early nineties. This alleged corruption of our identity by American mores has been a complaint for centuries, so there is nothing new in that strand of thought.

Here it is given a polish and rolled out as an actually quite effective lyrical theme. Over a plodding, almost comedic backing track, Bill Barrett’s simple trust in the freedom, affordability and choice he believes to be the hallmark of American life is simply placed in front of us in its absurd simplicity. A good square meal is 59 cents. The air is sugar free. Love can be found on a TV channel.

Of course, it is all fantasy. There is no ‘magic’ to American life at all. Bill Barrett’s dream is just that: a dream. A fantasy. As such, he is fair game for the leering, mocking chorus. The target, of course, isn’t America itself – but those who proselytise its marvels, often on nothing more than the evidence of a holiday.

While not a transcendent bit of pop, Magic America more than holds its own both thematically and musically.

15. This is a Low

This is, simply, a tour-de-force, and among the strongest tracks of not just Blur’s career, but the 90s as a whole. Musically, it is set among a shimmering haze of guitars and organ that somehow conjure up the feeling of a journey through foggy seas – which marries perfectly with the lyrical themes. Based on the famous inscrutable eccentricity of the British Shipping Forecast, the words mix those mysterious, unknowable places: Dogger Bank… Forth and Cromarty… Mallin Head.. .Bay of Biscay.

These names serve to create a vision of a Britain adrift amongst places of legend – somehow out of touch with the world outside itself. While this is literally ‘a low’, it is something that will always find you. In shorthand: you can take yourself out of Britain, but you can’t take the Britishness out of you.

To put it another – more emotionally allusive – way: no man is an island, but like an island can be surrounded by natural barriers that sometimes can’t be navigated. We are at once alone and part of a wider world – blind to our own idiosyncrasies.

There is also recognition of the fact that madness and humour is part of what we (mostly) consider our national heritage: even the Queen has ‘gone round the bend’. After two verse of psychedelia and allusion, she jumps off Lands End – the third allusion to ‘suicide’ of the album. In each case, these impulses are presented in a lightly comedic way. This could be a reflection of a certain shallowness to Albarn’s writing but a more generous reading would be that Albarn sees the absurdity of suicide. Coming so soon after the highly public and much venerated suicide of Kurt Cobain, and given that ‘Britpop’ was so consciously a riposte to grunge, it is hard not to see a degree of intent to Albarn’s treatment of the subject.

16. Lot 105

This wordless singalong is an amusing end to the album. With a keyboard sound straight out of every working man’s club jobbing entertainer’s toolbag, it builds into a frantic, punky pub track and ends on a suitably humourous end to Parklife – undercutting the drama of This is a Low in a very British way.

In Summary…

Parklife is a triumph: an elegant concoction of melodicism and musical invention that is rightly revered among the enduring artistic artefacts of its era. While never overtly idiomatic, it draws on a rich vein of both musical and lyrical inspiration from punk to disco to psychedelia to folk, and is played with absolute conviction and no small amount of skill. Coxon has long been established as one of the most inventive British guitarists of the last two decades, but he is more than matched by the solid (if unspectacular) drumming of Dave Rowntree and the freedom and melodic flair of Alex James on bass. Credit must also be given to Damon Albarn’s often unmentioned keyboard and piano parts, as well as Coxon’s contributions on saxophone. If Albarn perhaps lacks range and power as a singer, his adoption of a consciously English voice and pronunciation certainly helps to create the distinctive tenor of the album – and remains instantly recognisable 20 years on.

Taken together, the “Blur sound” of the mid-90s was sufficiently influential to remain detectable in any number of indie bands ever since – and arguably in the consciously London affectations of some British rap acts that have followed. Periodically, British music finds its voice in response to a perceived American invasion, and Parklife is a singularly successful endeavour in this regard.

In terms of lyrical heart and soul, an argument can be made that it veers perilously close to misplaced mockery of the common man (at best) or misanthropy (at worst) in parts, but generally, the spirit is warm enough to overcome most misgivings. Certainly at the time, the portrait it painted of Britain struck enough of a chord to help it shift millions of copies – and several of its songs survive on as popular culture touchstones. With the separation of time, perhaps it can be conceded that a handful of songs are audibly inferior to the album’s great moments, but overall this is an album truly deserving of its position in the popular pantheon of modern pop/rock. If it helped to spawn an annoying (and thankfully shortlived) trend for ersatz cockney pronunciation and rowdy choruses, that is no fault of such an accomplished album, but rather a reflection of the long shadow that Blur cast over the British music scene then and since.

Indispensable. Buy Parklife today 🙂