I know, I know – it’s an inflammatory title, but bear with me here – for I am NOT about to plunge into an argument about their relative contributions to The Beatles, who had the best post-Beatles career or which one wrote the worst tributes to their wives. Instead, I’m going to take a brief look at their contrasting styles as melodists and composers, starting with John Lennon and moving on to Paul McCartney whenever life allows me the time.

I know, I know – it’s an inflammatory title, but bear with me here – for I am NOT about to plunge into an argument about their relative contributions to The Beatles, who had the best post-Beatles career or which one wrote the worst tributes to their wives. Instead, I’m going to take a brief look at their contrasting styles as melodists and composers, starting with John Lennon and moving on to Paul McCartney whenever life allows me the time.

Now, both of the leading mop-tops were capable of writing in various styles – from rock ‘n’ roll to music hall, via country and folk (something else I will be looking at in a future post) but they also had distinctive styles to their original compositions. If you’re interested, and listen hard enough, they’re actually quite easy to spot. In a final post of this series (tentatively scheduled for 2022) I will also have a look at the instances where the two wrote in what might be considered atypical ways: i.e., when Lennon sounded like McCartney and vice versa.

Lennon’s Writing Style

Time signatures

It’s an oft-stated truism that Lennon primarily began with the words and worked towards a tune (certainly post the early Beatlemania days) and I think this shows up pretty clearly in a number of his songs. Metrically speaking, Lennon was far more prone to irregularity than his partner and this is often linked to the way in which the words inform the music.

Even in the earlier years of the Beatles’ career, this was apparent in a composition like No Reply (Beatles for Sale, 1964). Listen to the way the words of the title hit in the chorus. “no reply” is almost shouted – and it seems perfectly natural that it is followed by a crashing symbol and a chord change that lurches in a similar fashion.

[youtube https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=y-lHjQrFJQ8]

That kind of brusque impatience became more marked as The Beatles developed as musicians. In their early years, while adept at playing in various idioms, they stuck doggedly to the 4/4 time signature (with the odd foray into a waltz) but during what most consider to be their peak – 1965-1968 it was Lennon who largely drove the band into metrical irregularities – displaying a particular fondness for inserting bars of 3 or 5 beats into otherwise straightforward 4/4 songs.

Perhaps the most famous example comes in Lennon’s section to the McCartney-led We Can Work It Out (1965). McCartney’s section actually displays some uncharacteristically Lennonian deployment of pushed notes, but Lennon’s contrasting ‘middle 8’ (although such a term doesn’t mean much in this context) is a direct 3/4.

[youtube https://youtu.be/ZNfuTDbdKoY]

In She Said She Said (Revolver, 1966) the song switches signature from 4/4 to 3/4 at various points in the song – all of which helps to lend emphasis to key lyrics, as when the song segues into the rejoinder “when I was a boy”.

[youtube https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=34mL7eEhfK8]

Perhaps one of Lennon’s greatest gifts as a composer was his ability to make such changes appear perfectly natural. How many people have sung lustily along to All You Need Is Love (Magical Mystery Tour, 1967) without realising that the verse is largely in a 7/4 time signature (although some class it as alternating bars of 4/4 and 3/4, which would be in keeping with other Lennon songs).

[youtube https://youtu.be/CLEtGRUrtJo]

At it’s most extreme, Lennon’s musical trickery is seen in the famously arcane Happiness Is A Warm Gun (The Beatles, 1968), which trips through a wonderland of idioms, time signatures, key changes and tempi. In fact, so irregular was this song that ultimately the final version was created from an edit that spliced the first half of the song with the final ‘doo-wop’ section.

[youtube https://youtu.be/xTU2Y0VFH0E]

Ray Coleman’s famously scathing biography of Lennon (Lennon: The Definitive Biography) portrayed Lennon as a barely capable musician, and argued that such songs were the result of his musical illiteracy. Like many rock musicians at the time and since, it is true that Lennon had no formal schooling, but to argue that this was a detriment to his songwriting is patent nonsense. Dropping beats in unexpected places is exactly what makes these songs so Lennonion in character: form follows content. Having sang “all you need is love”, why hang about for an extra beat just to conform to a standard idea of what a bar of music “should” comprise?

In the general milieu of the times, many other artists were doing similar things. Most notably was perhaps Lennon’s most direct comparator Syd Barrett, who had a similar mental access to themes of childhood and a similar penchant for letting words dictate the pattern of the music that accompanied them. Other artists such as the mostly-forgotten Incredible String Band made such stylistic tricks their entire raison detre*.

Melody

Again, it is true broad a brush to paint with, but many of Lennon’s songs actually display very little harmonic movement – clustering around sequences of repeated notes, almost akin to a chant. This is a Lennonian trait identifiable as far back as Help! (1964). Sing the song unaccompanied, and you will find yourself basically singing a single note for most of the verse. In fact, take a couple of moments to listen to the original piano demo Lennon made of the song*

[youtube https://youtu.be/WXSjWGwbq1I]

Similar tracks abound in Lennon’s contributions to the Beatles’ discography – particularly during the ‘psychedelic years’ of 1966-68: Strawberry Fields Forever (Magical Mystery Tour, 1968), The Word (Rubber Soul, 1966), I Am The Walrus (Magical Mystery Tour, 1968) Come Together (Abbey Road, 1969), Tomorrow Never Knows (Revolver, 1966), I Should Have Known Better (A Hard Day’s Night, 1964), And Your Bird Can Sing (Revolver, 1966), Sun King (Abbey Road, 1969), I’m Only Sleeping (Revolver, 1966), Julia (The Beatles, 1968), Mind Games (Mind Games, 1973). All these tracks, while not being exactly monotone, display Lennon’s penchant for staying around a single note or two for long stretches – almost akin to a rant.

Again, I think this is partly a function of Lennon’s prioritising of words over music. In his early ‘message songs’ with the Plastic Ono band, this tendancy was at its strongest, in which the key words – “Power to the People”, “Give Peace a Chance”, “Woman is the Nigger of the World” – were emphasised more through a bluesy repetition than by a standalone melody as such.

“Drones”

As just discussed, Lennon was happy to use as few notes as possible in his melodies, so perhaps it is of little surprise that he also often wrote songs that clung, limpet-like to single chords. Perhaps the best example of a Lennon song par excellence in this vein would be Tomorrow Never Knows (Revolver, 1966), which satisfies itself with a single C chord throughout (albeit with a mild polychord of Bb overlaid in places).

[youtube https://youtu.be/6a3NcwfOBzQ]

Perhaps the earliest example of this tendency is found in Ticket To Ride (Help, 1965) which holds its opening chord of ‘A’ for repeated bouts of 15-20 seconds at a time.

[youtube https://youtu.be/VMxyK9azXR4]

In this, Lennon was undoubtedly influenced by George Harrison, who discovered Indian music during the filming of Help!

Other examples include Come Together (Abbey Road, 1969), Baby You’re a Rich Man (Magical Mystery Tour, 1967)

Descending Chords

Another Lennonian trick – done to death by imitators well into present times – is the descending chord change. Particularly prevalent in his finger-picking White Album era, Lennon clearly found it easy to pen attractive melodies over series of descending chords. McDonald, in his magisterial Revolution In The Head noted his fondness for the “semi-tonal slouch” and it present in many classically Lennonian tunes – particularly during the psychedelic years of 1966-1968, but also persistent through his solo work right up to his death. Here is 1980’s I’m Losing You.

[youtube https://youtu.be/E8KKH1Ce4Rw]

Other examples abound: Dear Prudence (The Beatles, 1968), Strawberry Fields Forever (Magical Mystery Tour, 1967), Lucy In The Sky With Diamonds (Sergeant Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band, 1967), Cry Baby Cry (The Beatles, 1968), All You Need Is Love (Magical Mystery Tour, 1967) are all good examples of how Lennon used a descending pattern as a foundation for his songs**

Conclusion

Lennon’s songs – at least those not written an existing idiom – display several characteristics: a drone note (either in melody or the underlying chord), descending chord sequences and brief excursions into metrical irregularity.

These characteristics have been turned into cliches in the hands of imitators such as Oasis but when allied to the musicality of the Beatles were clearly had that certain special ‘something’ that creates popularity. There’s an interesting debate to be had about how much Lennon’s essentially lazy musical vocabulary was only truly given shape when allied to McCartney’s skills in harmony and arrangement, but whatever your view, Lennon stands as a songwriter of great craft and guile, regardless of his limitations as a musician.

* I know that such simple tricks are mere nothings in the scheme of musical possibilities – and that prog rockers, folk artists and metallers have done far more extreme things – but they’re not under discussion here. Peace 🙂

** Mischievously, McCartney would parody this in his post-Beatles retort to Lennon’s public attacks on him Too Many People, which used exactly this kind of chord sequence under a chiding opening lyrical refrain of “piece of cake.”

[youtube https://youtu.be/0P_HKQGq730]

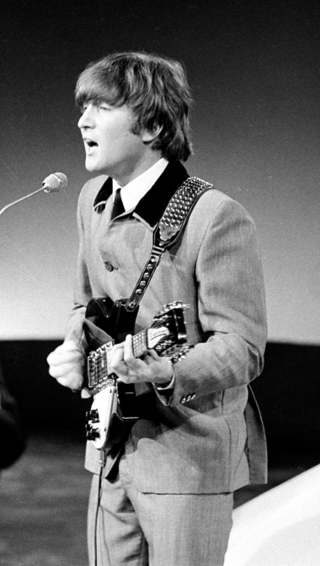

Image: John Lennon 1964 001 cropped” by John_Lennon_1964_001.png: VARAderivative work: GabeMc (talk) – John_Lennon_1964_001.png (originally Vereeniging van Arbeiders Radio Amateurs). Licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0 nl via Wikimedia Commons.