Note: this is part of the Britpop Album Showdown series.

Note: this is part of the Britpop Album Showdown series.

In many ways, Suede somehow fell through the cracks in the Britpop era. Perhaps the most artistically ambitious of the major players, they helped define the sound and attitude of the era and then fell apart at the height of their success, leaving them to toil in the shadows of the others who gladly ran through the door they’d helped to kick down.

Frontman Brett Anderson knowingly played with sexual ambiguity in a way that few artists aside from Bowie and Morrissey had successfully carried off. Indeed, to some degree this perhaps helped to overshadow the band’s musical achievements – the charge of being Bowie copyists or Morrissey wannabes was something they struggled to shake off, even as they settled in for a moderately long career with a changing lineup.

Their eponymous debut album had been greeted with laudatory acclamation by a British music press tired of reporting on the murky world and identity politics of grunge. Suede had a grip of the low life that would later be associated mainly with Pulp. They had the mantle of violence and arrogance that would be usurped completely by Oasis. They had a definitely British sound and approach that would be soon overtaken by Blur’s more openly popular sensibilities.

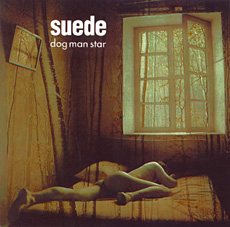

In the noon-bright milieu of 1994, their second album arrived just as the band disintegrated amidst drug use and personal acrimony – with guitar wunderkind and musical powerhouse Butler leaving the band before the album was even finished. While Suede would continue to produce singles and albums of quality, the feeling of unrealised potential never really left them, and left Dog Man Star as the peak of their achievements.

So: pull on your blouses, cock a snook at the straights and let’s get in there.

1. Introducing the band

Sounding as if purposefully designed as a scene-setting album opener rather than a song in its own right, Introducing the Band builds through atmospheric synth sounds to a pulsing psychedelic climax with a chanting persistence that recalls any number of 1960s Indian-inspired ‘drone’ tracks. The guitar lines are awash with reverb that is suggestive of the band playing in a huge empty hangar and (like much of the album) the mix is somewhat murky. Whatever it’s “meaning” – and I suspect it has none – it is a dramatic opening statement and darkly compelling in the manner of many of Suede’s finer moments.

2. We Are the Pigs

Brooding and full of menace, this showcases Suede at their most belligerent. Like many of Brett Anderson’s lyrics at the time, there is little objective sense here – it is more a string of images, which seems to concern street-level violence: perhaps in the guise of fascist repression (‘the pigs’ being of course one of the less flattering epithets applied to the police).

Depending on your taste, this style of lyric writing is either admirably poetic or wilfully obtuse. Possibly one reason that Blur, Oasis and Pulp were able to reach bigger audiences was partly down to the relatability of their words. Personally speaking, the air of mystery around what the hell is actually going on here works pretty powerfully for me, but I get why people might shy away from this kind of thing.

Musically, We Are The Pigs is a showcase for the muscular side of Suede that defies the popular effete reputation that seemed to be attached to the band – apparently purely because Anderson wore blouses. The divebombing bassline interlocks perfectly with a the type of orchestral and imaginative guitar track that Bernard Butler was so adept at. Blur’s Graham Coxon was similarly inventive, but his guitar was typically mixed ‘thin’ and held back in the mix. Nothing about Suede was ever held back in this way – and all the instruments seem to fight for attention. A special mention for those dark, sexy horn stabs after each chorus.

A great, dramatic swathe of dark pop music – at one utterly original and compelling.

3. Heroine

If more straightforward than We Are The Pigs, Heroine is still an exercise in broody allusion – and there is undoubtedly a play on heroine/heroin at work here, given Brett Anderson’s dalliance with the drug. Possibly he was personifying the drug as a woman (mysterious female ciphers have figured in the works of male songwriters for as long as there have been male songwriters) – and certainly there is something common to the erotic lure of sex and drugs: almost an intrusion into the male psyche. Opening with a quote from Byron (“She walks in beauty like the night”), Anderson takes us on a tour of barely sublimated desire for… something.

“She walks in the beauty of a magazine

Complicating the boys in the office towers

Rafaella or Della the silent dream

My Marilyn come to my slum for an hour”

As a song, the song deploys a pretty impressive set of dynamic tricks to lend what could have been a minor-key dirge in lesser hand an almost catchy quality. The shift in rhythmic emphasis during the chorus lends light to the shade. After the second chorus, an insistent, rising chord change (that probably classes as a middle 8) breaks into a stabbier, staccato version of the verse that serves further to stop any feeling of repetition.

4. The Wild Ones

If the tracks so far have been definitely “Suedian” in their sense of brooding drama, The Wild Ones is pure, power pop and breaks across the mood like sunshine through a crack in the clouds. There is little wonder that it was swiftly scheduled as a single – although the relatively small size Suede’s more singular audience saw it peak at just number 18 in the charts. It’s not hard to see that had this been released by a Blur or Oasis it would have charted much higher. Commercial speculation aside, this track (rating by Anderson as the peak of his collaboration with Butler) sets a relatable lyric of romantic escapism amidst a swooping landscape of strings and sinuous rhythm track, laced with poetic guitar runs.

The yearning of the words – with their talk of escape from suburbia in pursuit of love – touches on themes that have long been a part of British music, particularly the great writers of the English experience: Bowie, Weller, Davies and Morrissey.

Indispensable

5. Daddy’s Speeding

Returning the album to the darker vein, this haunted and haunting concoction was inspired by James Dean – although the allusions are so elusive as to be undetectable. This is the most overtly dramatic song on the album, with heavy, low piano notes punctuating the pretty, picked guitar chords of the verse that are reminiscent of the Beatles’ The Beatles (1968, aka ‘The White Album’). As with the other songs, Suede and their production team were seemingly unable to stay away from the reverb dial and – if we’re being critical of the band in the sake of balance – the effect can be a little soporific after a while. Not that you’d expect Suede to become the Housemartins, but listening to the album for the first time in some years it’s definitely noticeable that the production values act to some degree to smother the underlying song. The chugging, heavily-phased guitar of the chorus comes as a welcome respite and probably does just enough to keep the song out of self-parody.

Suitably for the lyrical content, the song ends in a coda of metallic noises that I guess is supposed to evoke a car crash.

I realise that this all might sound a bit dismissive of the song. Actually, I love the song and thing it’s one of the strongest on the album. We’re here to judge the album though – and in this context, Daddy’s Speeding seems to prolong a sense of gloom maybe a song or two longer than warranted. Compared to the way that Parklife seemed to have a natural internal rhythm, 5 songs in and it’s sort of easy to understand why the casual punter wouldn’t warm to a Suede album.

6 The Power

Ha! And as if to disprove the thesis I was busily expousing on the last song, hot on its heels is the lightest, slightest and poppiest song on the album. Famously pieced together by the band after Bernard Butler had left, it is unsurprisingly different in tone in his absence: shorn of his trademark guitar intricacies. It is also the most straightforward evocation of Bowie so far. In the shorthand of rock hagiography, Suede were always labelled “Bowie” copyists, but really this is the first song that really bears the print of his influence.

How so? Well firstly in terms of melody and construction – particularly the la-la-la sing-a-long coda – it has the hallmarks of Bowie’s early 70s heyday. Just the switch to acoustic guitar, bass, drums and (what I suspect is) a string quartet and you’re firmly in the Hunky Dory era in terms of sonic effect. Finally, the lyric itself concerns outcasts from around the world, be they from “the fields of Cathay,” “or enslaved in pebble-dash grave with a kid on the way” but is actually about the appeal of fascism. The protagonist is asking those downtrodden kids for the power: it isn’t about emancipating them.

Just give me, give me, give me the power

And I’ll make them bleed

Give me, give me the power

(Although I’m just the common breed)

Like Bowie’s fascination with how fascism takes root, this clearly isn’t about Anderson seeing himself as that kind of figure: merely observing how that sort of figure appeals to the young and the isolated. (Morrissey’s more direct exploration of this exact subject on the “National Front Disco (Your Arsenal, 1992)” attracted much ire, probably because it was much more on-the-nose).

In the context of the album, it does something to blow away some of the broodiness by dint of its light touch instrumentation and relatively jaunty tune. Indeed, it was slated as a fourth single release from the album, but the relatively poor chart performance of the next song put a kibosh on that.

7. New Generation

Following on from the slight but effective The Power, New Generation is 5 minutes of glitzy power pop which betrays none of the tortured genesis of its creation. Originally put together by Anderson and Butler, Butler left the band with this song unrecorded. His replacement was the then 18 year old Richard Oakes, with whom the band recorded the song. Butler’s absence is mainly felt in the lighter touch that Oakes brought to the band. While his guitar sound is in the same ballpark as Butler’s (presumably deliberately to keep it within the sonic identity that Suede had worked so hard to foster) his playing is noticeably more discreet.

The song itself is a relatively straightforward celebration of youthful potential and hedonism alike. Where Blur cocked something of a snook at youth’s dalliance of drugs and sex in Girls and Boys, Anderson probably hits closer to the mark with the line: “We take the pills to find each other”. Although the internet didn’t yet exist, Anderson could see the potential in love found down “the telephone wires”. Human connection can be found through technology… drugs… any medium. It’s irrelevant.

A sparkling triumph of a song. Had it been the lead single, Dog Man Star may have shifted more units than it ultimately did.

8. The Hollywood Life

Swapping the upbeat feel of the last two songs, this rowdy stomper returns to the swoopingly dramatic vocal lines and overwrought melodrama of the album’s first few numbers.

Lyrically, it takes an easy swipe at the industry of Hollywood stardom – particularly the way it treats women as sexual adjuncts to the main show. As with most of the lyrics on Dog Man Star, a direct reading is almost impossible to make, but “a hand-job is all the butchery brings” makes the intent pretty clear.

The songs grindy, lurching rhythm track and heavy guitar is saturated once more in that heavy reverb, and on the whole the effect is simultaneously striking, exciting but ultimately difficult to warm to. To some degree, this sounds a little bit like Suede-by-numbers. It has long been an aphorism of mine that a pop song better have some real meat on its bones to beyond 3 minutes in length, and I think a brutalised version of this song, stripped back to 2 minutes would have been more fitting than the full 4 minutes it subjects us to.

9. The 2 Of Us

Arriving after the contrived histrionics of This Hollywood Life, this is the sound of authentic emotion. Perfectly pitched at the more operatic end of Anderson’s baritone it is, for the most part, a perfect match of simple piano and beautiful vocals. Hearing Suede like this is a reminder that production actually really matters when it comes to pop records. Sometimes, just letting the instruments breathe is the best way to get the melody and words across: gimmicks like strings can be used to amazing effect (see: Still Life, on this very album) but can often serve to take away focus from the song they should be there to support.

The personal genesis of the song also seems clear. The voyeuristic side of Anderson – revelling in the seedier end of society’s preoccupation with sex and states of altered conscious plays well – but the authentic voice of his inner life occasionally shines through, and his sincerity helps to make this song both touching and memorable.

10. Black or Blue

Based again on piano, Black or Blue is a fabulously odd beast that tells us much about Suede’s concerns. Anderson’s angular vocal begins at the highest point of his range and tells a story – possibly about race or immigration: “There was a girl who flew the world from a lonely shore, Through southern snow to Heathrow to understand the law.” On arrival, however, the girl seems to fall for a man, and in their shared moment of love forget about nationality altogether – hence the (slightly barbed?) line of “I don’t care for the UK tonight.”

Again, I suspect your reaction to this song will be highly coloured as to whether you like the highly idiosyncratic product and Anderson’s wailing falsetto. As a song, the structure is quite classical in pop terms – there’s perhaps a little trace of Pink Floyd’s Us And Them (Wish You Were Here, 1975) in the song’s gently plodding piano and sighing half-tone shifts. All the weight for the song’s likeability or otherwise, thus falls on the melody line. As a youth, Black or Blue grated on me but listening back to it now I feel much more warmly disposed towards it. A 20 year slow burn, but still…

11. The Asphalt World

Your reaction to The Asphalt World probably depends on your capacity for concentration, your attitude to Suede in general and your taste for indulgence – for make no mistake: this is an indulgent song even in the context of an album of baroque extravagance like Dog Man Star. Over 9 minutes in length the song goes big on atmospherics and it is debatable whether the underlying song is strong enough to sustain interest for that long.

Lyrically, the song is typically obtuse, but swims in the same seedy seas as much of the album: lovers, lost in drugs, somewhere in the grimy underbelly of a featureless cityscape – the titular ‘asphalt word’: a forbidding, dark place without light and pity.

I know a girl she walks the asphalt world

She comes to me and I supply her with Ecstasy

Sometimes we ride in a taxi to the ends of the city

Like big stars in the back seat like skeletons ever so pretty

I know a girl she walks the asphalt world

Musically, the song accurately reflects this shapeless world insofar as it offers little melodic movement. Organs swirl out of the murk from time to time to punctuate things, and there are one or two moments of quiet and/or noise, but there are none of the swooning chord changes or sudden pick ups in tone that have been the hallmarks of the album’s best tracks. For the most part, the song drifts around the same couple of chords, and the descending riff that marks what I guess is the chorus (maybe the bridge?) doesn’t really Anderson anywhere to go with his voice. Butler noodles with his pedals… time passes… bits come and go… and then, eventually, that’s that.

For all its length, there is something almost unfinished about this song and – like This Hollywood Life – I think a pair of savage pruning shears would have served the song better. Of course, if you find the oppressive atmosphere compelling enough, then 9 minutes probably isn’t long enough, but for my tastes this is indulgence in service of an idea that just isn’t strong enough to support its own weight.

12. Still Life

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=P-RiRVmDOxE

….and by way of contrast, this is Suede operating at their absolute peak. An obscenely flamboyant track that builds from quiet, reflective acoustic fingerpicking through to the most operatic outro that sounds like nothing so much as Ravel’s Bolero channelled through the filter of Aaron Copland’s Rodeo. Here, the bombast is all in service of a relatable idea: an unrequited love – an unfulfilled life. In lesser hands, that is the subject of lame cliché, but Anderson finds a unique voice – both lyrically and in terms of performance (possibly his best recorded vocal) “Is this still life all I’m good for too?” he croons – a lyric that is both.

The orchestration is undeniably over the top, but I think there is something but admirable about it and probably slightly tongue-in-cheek. This incarnation of Suede was notably light on humour (search the lyrics all you like, you will find no gags: odd, in a band so supposedly influenced by Bowie and Morrissey) but I find it hard to believe that they weren’t exhorting the composer to these sort of over-the-tops heights without a smile on their faces.

In just over 5 minutes, the band (heavily augmented by approximately 2000 violinists, oboes, pianists, drummers and goodness knows how many pages of sheet music) Suede encapsulate the soul of this album in a way that the 9 minute grope of The Asphalt World couldn’t: the raging at the dying of the light… the vaulting ambition of the dispossessed… a howl at the empty shell of modern life. Triumphant.

Conclusion

Dog Man Star is a flawed, fascinating album. Perhaps the nearest analog for what it represents in the context of its time would be The Beatles’ White Album: like that, it was put together in an atmosphere of simmering interpersonal resentment and bursting to contain competing creative influences. It could probably never hope to be a unified artistic endeavour, but the tension itself contributed to a certain something in the musical atmosphere to the outcome that, if removed, would probably render it bland. Indeed, Suede morphed into a second life as a competent indie band after this – with a recognisable sound and a continuing lyrical interest in the same kind of subject matter, but shorn of the histrionics that informed their earlier work and culminated here.

Whether it can be judged to be “great” is probably down to your personal taste for melodrama and ambition. For me, it is undeniably great – but requires more commitment from you as a listener than the more accessible works of Pulp, Blur etc. Partly this is down to the nature of the music – several songs are more mood pieces (I’m looking at you, Asphalt World) than actual songs – but a lot of the blame or praise for it lies in the production. Most albums are concerned with capturing the authentic sound of the band actually playing, even when that itself is artifice. Dog Man Star however, is steeped in reverb and the overall effect over the course of 13 songs .

Despite these misgivings, there is no doubting the accomplishment of this album or its place in the Britpop pantheon. With a firmer hand on the creative tiller and more of a focus on cutting the creative fat, Suede could well have achieved greater commercial (if not necessarily artistic) success, but what they left as their legacy was a towering gothic construction unlike almost anything else from the era.