Or: looking at Bowie through the lens of Hunky Dory

And like that, he was gone.

Aside from friends, family and a small, trusted circle, Bowie had been apparently planning his exit for 18 months and – as it so often did for him throughout his career – it worked with masterful theatrical precision. Like many many people, I was diligently listening to surprising (and challenging) new album Blackstar on Friday and idly wondering/hoping that he might go on tour and give me the chance to see him in the flesh. Then suddenly he was dead and, like all the world, I was left mouthing like a fish on a deck. What the fuck?

The body of work left by Bowie is almost unimpeachable. Of course like any act who dares to dabble outside the kind of music for which he first became known his later work alienated some. Much of his 80s output is, for me, riddled with the awful stylistic ticks of that peculiar decade: there was something oddly mechanical about the way records were polished during that time that makes it hard to even listen to the songs underneath the production (see also: Pink Floyd’s post-Waters output, anything recorded by McCartney and the number of recent, successful re-imaginings of songs from the decade with stripped back instrumentation.)

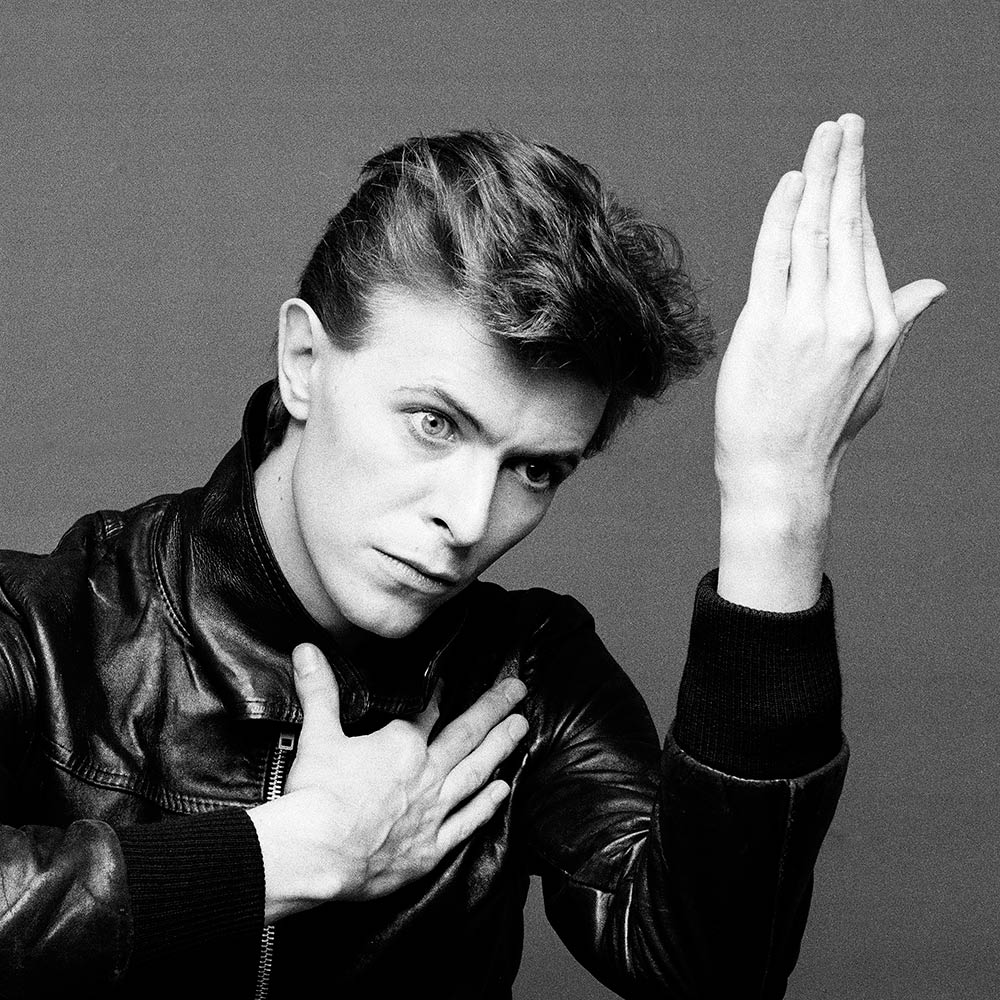

Of course, it the astonishing run of albums during the 1970s that defined Bowie’s legacy. Like The Beatles, Bowie was so in tune with the zeitgeist that he would absorb and reflect new ideas with such rapidity and conviction that it often appeared that he was the originator or arch manipulator. Bolan was first into eyeliner and glittery shirts, but Bowie defined what that meant. He didn’t invent ‘glam’ any more than the Beatles invented psychedelia, but he colonised it so completely, quickly and iconically that everything that came before seemed like a half-realised warm up act. Thus Bolan is a mere fond remembrance, while Bowie – arm draped louchely around Mick Ronson’s shoulder on Top of the Pops – is icon.

Of course, it the astonishing run of albums during the 1970s that defined Bowie’s legacy. Like The Beatles, Bowie was so in tune with the zeitgeist that he would absorb and reflect new ideas with such rapidity and conviction that it often appeared that he was the originator or arch manipulator. Bolan was first into eyeliner and glittery shirts, but Bowie defined what that meant. He didn’t invent ‘glam’ any more than the Beatles invented psychedelia, but he colonised it so completely, quickly and iconically that everything that came before seemed like a half-realised warm up act. Thus Bolan is a mere fond remembrance, while Bowie – arm draped louchely around Mick Ronson’s shoulder on Top of the Pops – is icon.

Musically though – and that is the theme of this blog, after all – Bowie had the rarest of gifts: being able to move across genres while remaining recognisably himself, whether dabbling with jungle (Earthling, 1997), free jazz (Blackstar, 2015), polished 80s pop (Let’s Dance, 1983) or chilly European synth music (Low, 1977)

His songwriting style was recognisable but his use of arrangement and production dazzling diverse. If we’re being honest, many artists of the late 1960s might have conceived Space Oddity in response to the moon landing, but on this – Bowie’s first true statement of intent – the pieces are already in place: thematically about man as an alien, verbalised in a quite and very English-poetic way (a hint of twinkling cockney barrow boy under the studied vocal mannerisms) and a very idiosyncratic construction. Bowie’s lifelong dalliance with acting is all there on his first day at work – the construction of an entire persona sat playfully on the line between the self-revelatory and the detached observer of a world gone mad.

Strip away the drum ‘n’ bass underpinnings of ‘Little Wonder’ (Earthling, 1997) and the song itself could have slotted neatly into the middle of 1973’s Aladdin Sane.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=UT2oqEHwvUY

So regardless of what Bowie was doing, Bowie was always Bowie. With 27 albums, 111 (!!!) singles and more stylistic diversity than you could ever hope to shake a stick at, it is next to impossible to study Bowie’s work in coherent form.

So 1972’s Hunky Dory remains my own personal favourite of Bowie’s albums (and Kooks my favourite of his songs) and the best starting point for potential students of what-made-Bowie-Bowie. With that in mind, let’s dive into the album and – track by track – unravel the essence of the man’s art.

Changes

Ah. What a tune! How many ideas can you stuff into 3:33? A boogie-woogie progression… a piano ballad… an obscenely catchy chorus hook and a dawdling, melancholic sax outro.

Bowie primarily composed on guitar and piano (although his first love was the sax) and listening to his music I often get the sense that he would write little pieces that he would later stitch together into a whole (a trait which, if true, he would share with Lennon). Changes is somewhat emblematic of Bowie’s output in this regard. The song is a perfect construction of diverse elements that, examined rationally, don’t logically ‘fit’. The boogie-woogie piano riff that introduces each verse really neither belongs to the verse nor the chorus, but of course is a great intro – which is often all a song needs.

Another “Lennonian” Bowie staple was the chunky, expressive chord change designed to fit a specific lyric – in this case the little passage that ends each chorus (“time may change me… but I can’t trace time.”) Whenever this trick is used it serves

Lyrically, the song is a masterclass in Bowie lyricism. Only 27 and yet to become a mega star at the time, the theme of age seems like an odd one to tackle, but Bowie is arch enough to recognise that rock ‘n’ roll already had an internal cycle of change and rebirth, action and reaction. Given that rock ‘n’ roll was still just 13 years old at the time of the song’s recording it shows remarkable prescience on Bowie’s part. Arguably, the melding of jazz, boogie-woogie and pop melodicism of the music itself contains part of the song’s message: music changes as people change.

Oh You Pretty Things

If Changes is suggestive of an odd state of pre-nostalgia, Oh! You Pretty Things looks stridently to a future beyond traditional sexuality. Musically, the song evasively shifts through keys and rhythms throughout its solo piano/vocal verses before exploding into a triumphant chorus that follows the classic descending chord trick that all songwriters have, at some point, used to their advantage.

Lyrically, the song begins with a domestic scene. The protagonist (as with many Bowie songs, there is no clue whether the main actor is Bowie himself or the singer simply adopting a voice) awakes next to – we assume – a lover. Puts wood on the fire and boils the kettle. Looking through the window, the sky “cracks” and an ambivalent future is seen in the manner of a vision. A hand reaches down and the protagonist becomes prognosticator – seeing a world where a new “race” has been born shorn of the trappings of the past. The “golden ones” are these coming, post-sexual beings – and I think we can assume that Bowie probably considered himself to be in that vanguard at this point.

This might drive mamas and papas insane, but in the end “homo superior” will be… superior. And award yourself absolutely no points for guessing the subversive intent of the word ‘homo’ here. The path blazed by the likes of Bowie and his youthful fellow-travellers (“the Golden Ones”) will literally write the book for future generations.

As with Changes, this shows remarkable prescience in its social commentary but there may be a little tongue in cheek at work. Bowie was a provocateur at heart, and it’s hard to say how seriously he was positing such a change in the gritty milieu of early 1970s Britain. he famously claimed to be gay or bisexual himself in interviews, but by 1980 had come to regret that claim. On that basis, this seems more to be an early case of Bowie flirting with different sexual identities as an actor – posing “what if?” questions rather than making a serious statement of intent.

Still: brilliant

Eight Line Poem

Musically, Eight Line Poem is barely there. A relaxed, bluesy meandering trip around 4 heavily-flanged piano chords, bolstered by some Stones-y Mick Ronson guitar work. As the title suggests, the piece is more of a poem set to music rather than a properly constructed song. There is something idle and half-sketched about the enterprise – although it touches on a theme that rock musicians on constant tour recognise: hotel rooms, boredom, loneliness. Something about it suggests to me an American setting: “the key to the city, Is in the sun that pins, the branches to the sky” is hardly redolent of, say, Birmingham.

An interesting companion piece to this would be Pink Floyd’s Nobody Home (The Wall, 1979)

Life On Mars

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=v–IqqusnNQ

Wow. Is there anything that can sensibly be said about this in 2015 that hasn’t been said a thousand times by a thousand better writers? Possibly not. Still, we can hardly ignore this touchstone in not just Bowie’s career but in the whole pop-music-as-art-form that has rung through popular discourse since Elvis first thrust his pelvis into the world’s face.

Like many of Bowie’s songs of this period, this fabulously rich from a musical perspective. Dissonant but ‘natural’ lurches in key, and what seem like awkward diminished and augmented chords to the guitarist speak to its definite origin as a piano piece. Bowie was a competent enough pianist, but here it is left to Rick Wakeman to make the most of the chords – using inflections from classic music and rich, baroque runs of notes to lay a background for the string quartet that whips the song to a swooping, cinematic climax.

Of course, pop had been yoked to orchestration since the day that Sinatra first swung. Pop artists from the mid-60s onward had used classical allusions and structures under the auspices of prog rock, and it was already 7 years since the Beatles stunned their audience by the instrumentation on Yesterday. Partly, Bowie is feeding on that tradition, but there is a huge slice of the drama queen in both his vocal performance and the arrangement. Just listen to the way he sings “Oh man!” and you instantly understand that Bowie is both present in and distant from the action in the lyrics.

The girl hooked to the silver screen is part of the action, just as the bystanders watching lawmen beating up the wrong guy are part of the action, and just as surely Bowie singing about them all is part of the action in turn. Today, we consume real life as entertainment and the lines between them are increasingly blurred. Bowie could see that coming all the way back 44 years ago. In this light the question “is there life on Mars?” is an oblique way of asking is there life in us – or we all just cold observers of our own lives and the lives of others? A recurrent lyrical theme for Bowie as it was for Lennon – and it is probably no coincidence that they were both voracious consumers of culture.

Kooks

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=EsSlOGzPM90

Another one! The fourth stone-cold classic in five songs. The titular ‘Kooks’ in question are Bowie and then-wife Angie, but the song is addressed to their newborn son Duncan. As befits a song addressed to a child, there is a playfulness to both the melody and delivery of the lyrics. It is literally a children’s song – complete with oompah bass, chortling trumpet parts and a simply joyous piano counterpart melody in the second chorus.

Lyrically, it is the most obviously personal song on Hunky Dory. There is no archness or artifice here – unless it’s in Bowie’s delivery, in which he adopts a comically self-deprecating ‘old man’ voice (“I’m not much cop at punching other people’s dads”). Lovely, warm, earnest and funny alike, no other song has ever touched so directly on the subject of fatherhood and for this reason – and its personal resonance – it is my favourite of Bowie’s songs – a cheerful riposte to, say, Kate Bush’s This Woman’s Work (which I love for different reasons). For 3 minutes, Bowie’s mask drops and we are allowed to see the ‘real’ man behind the make up and the glitter: a contented dad with a bit of cockney about him.

Quicksand

If Kooks is directly about Bowie’s “real” life, then Quicksand is all about the surface artifice of the public artist. Musically a near 8 minute treatise on self knowledge wrapped in a fug of sweeping chord changes and ornamental pianos it could be seen as a slightly poorer cousin to Life On Mars? but lyrically it posits questions of everyone’s potential not for self realisation, but to be drawn into fascism and war if you fail to look beneath the superficial veneer of appearance.

The power of a Himmler (or a Churchill) is in the attractiveness of their ideas and how they are presented. Where in paraphrase Life on Mars? asks us to “look at all the artifice around us”, Quicksand adds an important “but…”.

Artifice is the tool by which tyrants drag us into their wars and worldview. Again, given the overarching lyrical concern of Bowie with his own artifice (and his ambiguity towards that artifice) it is no surprise to hear him admit that “I’m not a prophet… Just a mortal with the potential of a superman…tethered to the logic of Homo Sapien.” If we as people have to be careful not to get sucked into believing the lies of propagandists for one thing or another, we also have to be mindful of believing in mere pop stars like Bowie. Double irony here, given the millions of words being spoken about the man right now. Treble irony if you include this.

Since his death, I have given this theme a lot of thought and it’s interesting that Bowie made very little overt political comment in his life. He dabbled with the iconography of fascism in the mid-70s ‘Thin White Duke’ phase of his career, but he wasn’t given to what we would recognise as political activism. Some – the Bonos, Chris Martins and Morrisseys of this world – seem to struggle to mistake their public prominence with the profundity of their own thoughts, as if they became famous because of their bleeding hearts rather than that being an unfortunate side effect of twats becoming famous.

Bowie was always too smart to fall into that solipsistic trap and once again shows his remarkable prescience: it was still 14 years before Live Aid made public shows of virtue de rigeur among the pop set.

Fill Your Heart

Musically, this is another rollicking piece of piano barrelhouse fun – almost an extended riff on the countermelody playing during the chorus of Kooks. Reading the lyrics, it is tempting to suggest that like that song it is directly addressed to someone and – as with some of the other songs – a plea for reality over artifice. Even real things that happened in the past are now “only in your mind.” If you wanted to get all analytical about things, you might note that the most direct and relatable songs are also the simplest musically. Whereas Life on Mars? is a barrage of instrumentation, chord changes and ideas, Kooks and Fill Your Heart are simple both in message and intent.

To draw another Beatles parallel (sorry: they’re just my personal songwriting yardstick) McCartney’s solo albums are full of songs of this type, which is perhaps why for most people they lack the emotional resonance of the best of the Beatles’ work. Once unbalanced by the loss of Lennon, McCartney drifted into inanity. Perhaps the most rewarding aspect of Bowie’s self-awareness was being able to act as his own silent partner. Or, perhaps it was a function of his life long habit of seeking collaborators to ensure that his mind stayed sharp and he didn’t drift into facile indifference to his own work. Either way, Hunky Dory’s weightier themes could easily become oppressive if not lightened by excursions into relative froth like this. As a final aside on an even broader theme, this is perhaps why the decline of the album in favour of single track downloads means it has become harder for acts to find an audience – as they have no canvas on which to paint the full range of their interests and stylistic influences, ending up instead stuck with A Sound from which their audience won’t permit them to resile. Or they might just be boring (hi, Coldplay!)

Andy Warhol

Beginning in eerie synth obscura and with a random snippet of conversation between Bowie and an unheard sound engineer, Andy Warhol is a dark concoction after the pallet-cleaning Fill Your Heart. Based on minor chords with a flamenco-type rhythmic construction and slipping into a dissonant, atonal coda, it is very much a mood piece that is, perhaps, difficult to warm to – unless you listen to certain lines of the lyrics, which undercut the dark mood somewhat (“Andy take a little snooze… he’ll think about glue

What a jolly boring thing to do”).

If we wanted to get arch about it (and possibly over-read matters) the subject of the song – i.e. Andy Warhol himself – was difficult to warm to. Warhol was aloof and probably too-clever-by-half, Bowie probably identified with the way he viewed other as mere adjuncts to his own art (elliptically returning to the theme of Life on Mars?) Bowie enjoyed Warhol’s presentation but there is an element of lyrical condemnation of the way that he blurred art and life and perhaps a warning note from Bowie to himself not to: “Dress my friends up just for show”

All ways up, Andy Warhol is probably the weakest track of Hunky Dory, musically unsatisifying and not striking quite the right balance of light and shade that makes the rest of the album so very majestic.

Song For Bob Dylan

If Warhol the person was the very personification of artifice as art, Bowie turns his eye to the opposite end of the spectrum (again: the strength of the long playing format allows/allowed artists to do this kind of thing). Dylan as a figure in the public consciousness has always been about “authenticity.” If Warhol was all sunglasses and crowds of weirdos, Dylan was some a guy from out of nowhere who stood there with an acoustic guitar and sang the truth – as Bowie directly reminds us in the first verse: “His words of truthful vengeance, They could pin us to the floor.” Of course, given Bowie’s fascination with fame and artifice, he can’t resist reminding us that even “Bob Dylan” is a goddamn showbiz pseudonym off the bat: “here comes Robert Zimmerman.” And even “David Bowie” was a pseudonym adopted to avoid confusion with the already-famous Davey Jones of The Monkees. Layers upon layers. Glass onions, man.

As an aside – I hope if you had any lingering doubt that there is a resonant theme to Hunky Dory (and by extension to Bowie’s entire body of work) is has been been dispelled by now.

Again, it is probably no coincidence then that the music of Song for Bob Dylan is the most ‘traditional’ of the songs on Hunky Dory. With an bluesy opening guitar figure that pretty much quotes the opening riff of the Freebird by the famously rootsy Lynyrd Skynyrd and a chugging rock chorus with some of the swagger of the Rolling Stones late-60s output, it is the very antithesis of Andy Warhol. Bowie maybe even obliquely hints at this in the words of the chorus: “…a couple of songs, From your old scrapbook…“.

Queen Bitch

An invigorating slice of proto punk, Queen Bitch is another outright classic and stands out even in this sea of excellence. Where Song for Bob Dylan laid back on a comfortable, country-blues vibe, Queen Bitch crackles with an urgency befitting its subject matter: the scrambled, chaotic lives of people living on the margins: druggies… whores… the sexually ambiguous. Like its subjects, it is scattergun: starting with an Eddie Cochran riff before leaping in its own mad directions – slipping between keys and tones, no two passages being exactly the same and all soused in Mick Ronson’s squawling, undisciplined guitar.

The world Bowie documents here is, of course, alien to the majority of people and something he himself probably only came to experience by hanging out in the seedy underbelly of Lou Reed’s New York (Bowie produced Reed’s masterwork Transformer that same year). Reed’s work is visceral, direct and stems more from direct involvement, but in Queen Bitch, Bowie is a wry, thrilled observer “up on the eleventh floor, watching the cruisers below” but can feel the dark allure of the whole scene (“it could’ve been me“).

Again, if we return to what I’m grandly calling the narrative of Hunky Dory, we see the distance between Bowie and the people he’s observing. He can slip into their world, savour it and even participate but is self aware enough to get out (at least at this stage in his life, by the late 70s all such arch self-awareness was very nearly lost in a blizzard of cocaine). And of course, this in turn fed into the mythos that was “David Bowie” the overarching persona of his career.

The Bewlay Brothers

…and so to The End. The Bewlay Brothers shows Bowie at his most enigmatic, closing Hunky Dory on a fascinatingly inconclusive (but thematically apposite) note. High-falutin’ nonsense poetry (“In our Wings that bark, Flashing teeth of brass“) rubs shoulders with comically out of place cockney asides (“Lay me place and bake me pie, I’m starving for me gravy“). In this regard, I’m reminded of nothing more than that other icon of strange, English sexual otherness: Kenneth Williams.

As we’ve seen with other tracks from this album, the music is the perfect match for this weird, displaced wordplay – reaching its conclusion in disquieting oddness. Having revealed – or hidden – so much throughout the course of the album, it feels that Bowie seemed it could only be appropriate to end on a slice of otherworldly alienation – all hints and no answers – a kind of psychological dare: “Even if I know that you know that I know, and our ‘relationship’ as artist and listener is already pretty complicated… try picking the bones out of this“. Again, I’ll draw a parallel with Lennon, who conjured up the lyrics to I Am The Walrus out of a sheer Dylan-gets-away-with-bloody-murder wantonness and yet somehow found a theme emerge from the ensuing silly wordplay.

I suspect that The Bewlay Brothers is the kind of track that people skip when listening to Hunky Dory, and I can understand why: on an album so laden with an self-referential conversation about the nature of the public vs. the private Self, it is a slice of almost wilfully obscurantism that is difficult to relate to and, frankly, doesn’t have much of a chorus. As such, it is more of an artistic exercise than a song in itself. If you were to be unkind, you would drop it in the bin marked ‘self indulgence’, but in the wider context of Hunky Dory, I see it more as a final statement of intent: Bowie saying that regardless what you think he’s revealing through my music, you’ll never actually know what is truth and what is nonsense. It’s the final layer of icing on a mile deep cake.

Hunky Dory in conclusion…

Phew. That was some trip – and hopefully enlightening as to why Bowie had such resonance as an artist. He was arguably the first pop star to sing coherently about being a pop star and what that meant on a personal level: documenting the fascinating, complicated nexus of the day to day reality of trying to live a reasonably normal human life when people invest so much meaning in the one side of you that happens to show up on TV. And while we might not all be in the public eye to the same degree, we all wear masks to suit the company we keep. We come to work and smile through the day to hide our private pain (or perhaps we spend the day writing long blog posts when we should be working).

All of human life is artificial to some lesser or greater degree, otherwise we would just be animals like the rest – and to see what misanthropy results from believing that latter proposition, check out Roger Waters’ bleak later output.

Hunky Dory then is Bowie in microcosm. Using his fame to hide himself in plain site – adopting a persona to create distance between the day to day man and the very public figure. Bowie wasn’t the first performer to do that (recall us to the pseudonyms: “Billy Fury”, “Tommy Steele”, “Johnny Storme”) but he was the first to address this directly through his own material. Best of all? He pulled the trick off and hid it all under some fucking killer choruses.

Even if all cod-intellectual flimflam sounds alien to us poor schlubs working in offices, it is part of the very human experience we all share. That Bowie included the freaks and the outsiders in the gamut of his artistic vision is why he resonated so strongly with those crowds, but there was a universality which meant that people who truly hated Bowie are pretty thing on the ground.

Rest in peace, you crazy, starbound genius.